overview of solitary thyroid nodules

The thyroid gland is a small, butterfly-shaped endocrine gland located in the front of the neck, just below the Adam’s apple. It is composed of two lobes connected by a thin isthmus and is responsible for producing thyroid hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which regulate metabolism, energy levels, and overall growth and development. The gland also produces calcitonin, a hormone that helps regulate calcium levels in the blood. The thyroid is highly vascular and depends on iodine intake to synthesize its hormones. It is controlled by the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis, with the pituitary gland releasing thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to regulate its activity. Disorders of the thyroid, such as hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, or nodules, can significantly impact overall health and require careful medical management.

Solitary Thyroid Nodules

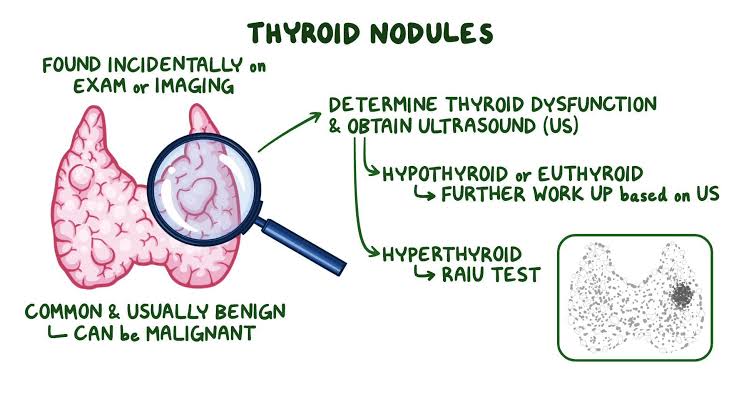

Solitary Thyroid Nodules refer to a single lump or mass in the thyroid gland, which can be benign or malignant. Most thyroid nodules are benign, but a small percentage are cancerous, so evaluation is crucial to determine their nature.

1. Causes (Etiology):

• Benign Causes:

• Colloid Nodules: The most common type, usually benign growths due to overproduction of thyroid cells.

• Follicular Adenomas: Benign tumors of the thyroid follicular cells.

• Cystic Nodules: Fluid-filled nodules that can arise from degeneration of solid nodules.

• Thyroiditis: Inflammation of the thyroid, such as in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or subacute thyroiditis, may present as nodules.

• Multinodular Goiter: A single nodule in a thyroid otherwise involved in diffuse enlargement (goiter).

• Malignant Causes:

• Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: The most common thyroid cancer, typically slow-growing but can spread to lymph nodes.

• Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma: A type of thyroid cancer that may spread to other organs, such as bones or lungs.

• Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Arises from the parafollicular cells (C-cells) and may be associated with genetic syndromes like MEN2 (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2).

• Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A rare, aggressive form of thyroid cancer.

• Lymphoma: Rarely, thyroid nodules can be due to lymphoma of the thyroid.

2. Risk Factors:

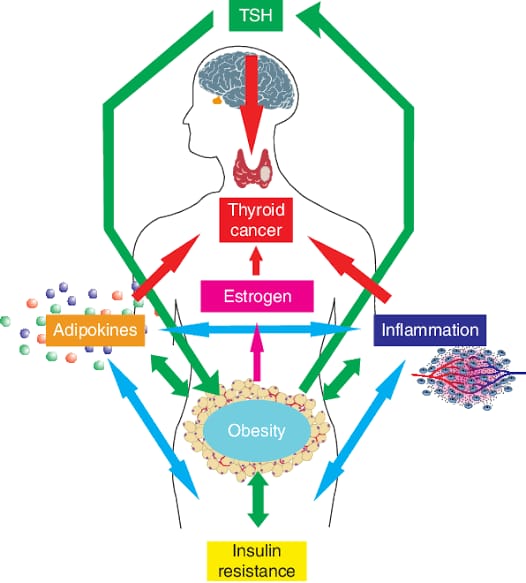

• Age and Gender: Women are more likely to develop thyroid nodules, especially as they age. However, nodules in men and those under 20 or over 60 have a higher likelihood of malignancy.

• Radiation Exposure: A history of radiation exposure to the head, neck, or chest, particularly during childhood, increases the risk of thyroid nodules and cancer.

• Family History: A family history of thyroid cancer or genetic syndromes like MEN2 increases risk.

• Iodine Deficiency or Excess: Both iodine deficiency and excess iodine can contribute to nodule formation.

• Chronic Thyroiditis: Inflammation of the thyroid, particularly in conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, increases the risk of developing nodules.

3. Pathophysiology:

• Benign Nodules: These are typically caused by localized hyperplasia of thyroid cells, often due to genetic mutations or external factors such as iodine deficiency.

• Malignant Nodules: Malignant transformation may occur in thyroid follicular or parafollicular cells due to genetic mutations (e.g., RET mutations in medullary carcinoma or BRAF mutations in papillary carcinoma).

• Autonomous Function: Some nodules, especially toxic adenomas, may function independently of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), leading to hyperthyroidism.

• Cyst Formation: Degeneration of pre-existing solid nodules can lead to cystic changes, where the nodule becomes fluid-filled.

4. Signs and Symptoms:

• Asymptomatic: Many solitary thyroid nodules do not cause symptoms and are discovered incidentally during a physical exam or imaging studies.

• Visible Lump in the Neck: The most common presentation is a painless lump or swelling in the front of the neck.

• Compression Symptoms:

• Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), breathing (dyspnea), or a sensation of pressure in the neck.

• Hoarseness or voice changes if the nodule compresses the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

• Thyrotoxicosis Symptoms (if the nodule is hyperfunctioning):

• Weight loss, tremors, palpitations, heat intolerance, and increased sweating.

• Pain: Sudden onset of pain in a thyroid nodule is rare but can occur with hemorrhage into a cystic nodule or with thyroiditis.

5. Laboratory Investigations and Findings:

• Thyroid Function Tests:

• TSH:

• Low TSH may indicate a hyperfunctioning (toxic) nodule, suggestive of hyperthyroidism.

• Normal or elevated TSH is more common in non-functioning or potentially malignant nodules.

• Free T4 and T3: Assessed if TSH is abnormal.

• Thyroid Antibodies:

• Positive anti-thyroid antibodies (Anti-TPO) may indicate underlying Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

• Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) Biopsy:

• The most important diagnostic tool for determining whether a thyroid nodule is benign or malignant.

• Cytological analysis can identify benign conditions (colloid nodules, cysts) or malignancy (papillary, follicular, medullary carcinoma).

• Ultrasound (US):

• Helps assess the size, structure, and composition (solid, cystic, or mixed) of the nodule.

• Suspicious features for malignancy include hypoechogenicity, irregular margins, microcalcifications, increased vascularity, and a taller-than-wide shape.

• Radioactive Iodine Uptake (RAIU):

• Used to evaluate the functional status of the nodule (hot vs. cold nodule).

• Hot nodules: Nodules that take up excess iodine are typically benign and produce excess thyroid hormones.

• Cold nodules: Nodules that do not take up iodine are more likely to be malignant.

• CT or MRI:

• Rarely used but may be necessary to assess for local invasion or if the nodule extends into the chest.

6. Treatment:

• Observation:

• If the nodule is small, benign, and asymptomatic, regular monitoring with ultrasound and clinical exams is recommended.

• Thyroid Hormone Suppression Therapy:

• Some physicians may use levothyroxine to suppress TSH in an attempt to shrink benign nodules, though this is controversial and not commonly used anymore.

• Surgery (Thyroidectomy):

• Indications for surgery include large nodules causing compressive symptoms, suspicion or confirmation of malignancy, or patient preference.

• Options include a lobectomy (removal of one thyroid lobe) or total thyroidectomy (removal of the entire thyroid).

• Radioactive Iodine Therapy (RAI):

• Used to treat hyperfunctioning (toxic) nodules. RAI destroys the overactive thyroid cells.

• Ethanol Injection or Laser Ablation:

• Minimally invasive procedures used to shrink benign cystic nodules.

• Thyroxine Therapy (Post-Thyroidectomy):

• Following surgery, patients may require lifelong levothyroxine replacement therapy to maintain normal thyroid function.

7. Complications:

• Malignant Transformation: Although rare, benign nodules can transform into thyroid cancer over time.

• Thyroid Cancer: Some solitary nodules may already be cancerous at diagnosis, necessitating surgical treatment.

• Compression Symptoms: Large nodules can compress adjacent structures, leading to difficulty swallowing, breathing, or voice changes.

• Hyperthyroidism: Autonomous, hyperfunctioning nodules may cause excessive thyroid hormone production, leading to hyperthyroidism and its associated complications (e.g., atrial fibrillation, osteoporosis).

8. Prognosis:

• Most solitary thyroid nodules are benign and can be managed conservatively with monitoring. • Malignant nodules, particularly papillary thyroid cancer, have an excellent prognosis with appropriate treatment (surgery and, if necessary, radioactive iodine therapy).